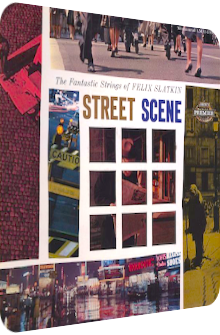

Felix Slatkin

Street Scene

1961

American conductor and violinist Felix Slatkin (1915–1963) is the man for Space-Age strings. Wait, wasn’t that Les Baxter? Indeed, but whereas Les Baxter augments both his own compositions and the renditions of classics with electrifying percussion and different textures, Slatkin is keen on letting the listener absorb the surface quality of the strings more than anything else. Street Scene, however, is a different road!

Released in 1961 on Liberty Records, the album sees Slatkin and the marketing buffs come up with a nice concept that is admittedly easy to envision for a major label, but still not applied to all too many works after all: 12 compositions about streets. Spare me the drum roll, don’t raise your fist, but this is exactly what the listener is going to receive… or rather not. Street Scene does not care for parks, alleys, crossroads and traffic lights, nor is it depicting riots, cold nights, trash and ghettos that are weighty parts of big cities, nope, this is a Space-Age album which believes in the good of mankind and the merit of technocracy. The result is the superimposition of glowing string cataracts, mellowed horn illuminants, high-rise flutes, metallic drums and quirky harpsichord addendums. In fact, the only earthen instrument is probably the accordion. You see where this is going, Street Scene absorbs the principal idea of its 12 street-worshipping enchantments and then augments the tone sequences in order to lift off. Bird’s eye perspectives instead of city strolls are key to the LP. The strings are always in the epicenter, but a welcome progression does take place. Read more about it and the other aural achievements in the following paragraphs.

I shall not complain if a presumably earthbound, street-prone album kicks off with a downright elysian transcendence, although it doesn’t feel right. But what the heck, Alfred Newman’s title-lending Street Scene opens the album in a superb fashion. Felix Slatkin’s string orchestra camouflages the Waltz structure of the original as efficiently as possible, only the argentine snares and the rhythm in 3/4 time hint at the roots; there’s anything wrong with a Waltz anyway, but here its rhizomatic approach lifts into lilac lands, fueled by positively pompous violins, a granular lead guitar and a choir of humming singers from space. To be honest: Street Scene is quite a bit melodramatic and over the top, but its good-natured nucleus prevents it from fully sliding into the cesspool of chintziness. Al Dubin’s and Harry Warren’s Boulevard Of Broken Dreams follows as a great counterpoint, as it feels much emptier, lets the darkness in via a coquette’s accordion-underlined lamento and illumines the threnody with fresh flutes and grave strings. Although the withdrawal is never overcome, flashes of nostalgia are evoked.

Alan Rankin Jones’ Easy Street fortunately resurrects the aureate bliss of the opener and would even make Neil Hefty, the creator of the theme from Odd Couple, a tad envious due to the rhythmic harpsi-/clavichord staccato whose granulative shards provide the crisply pulsating aorta to the wonderfully warped string washes. This is Easy Listening par excellence, inheriting the most positive fibers of the otherwise dubious genre. Up next is On The Street Where You Live by Al Lerner and Frederick Loewe, a swinging flute-bolstered midtempo embracement of the concrete jungle that is called world. Pizzicato droplets, sun-dappled chords of Rimini and a fully fleshed out high-chromaticity polyphony, this tune has it all, but ventures into a fairy tale here and there, possibly making this a no-go for quite a few people, I imagine.

The quirky Pigalle by Georges Ulmer and Géo Koger is equally dichotomous due to its bucolic wideness. The strings are vivid and strong, the accordion-based fairground atmosphere, however, exudes the smell of cotton candy, even though a real barrel organ is amiss. Side A ends with a gorgeous interim apotheosis called Street Of Dreams. Originally envisioned by Sam Lewis and Victor Young, this sweeping ballad is oneiric as can be, supercharged with mauve-tinted strings, female choirs and a delightful amount of harp glissandos. Even silky horn layers appear in order to augment the harmony. A great piece for lovers and, er, fans of the 101 Strings’ The Exotic Sounds Of Love (1972).

Side B continues the asphalt-loving dreamwave approach of Felix Slatkin and his orchestra. Be it the reappearance of material written by Al Dubin and Harry Warren in the opening slot called Lullaby Of Broadway with its cheeky xylophone vesicles, smashing drum dioramas, happy harpsichord helixes and swinging brass protrusions amid the mirage of string whirls, or Felix Slatkin’s very own follow-up The Streets Of Laredo whose Flamenco bonfire guitar and whistling gringo add a pinch of Texas feeling in an otherwise aeriform place, the album remains in a state that is curiously detached from the ground floors or street lights and rather ventures into the air, looking at its locales from above. Frank Loesser’s Standing On The Corner surprises with clarinet murkiness in-between the scintillating interstices of carefreeness as nurtured by the flutes and cautiously spy-evoking timbre, and even Lonely Street by Carl Belew, Kenny Sowder and W.S. Stevenson alters the formula with a distant mixed choir – which admittedly has been presented before –, slapped bass guitar strings and mountainous brass billows.

Dorothy Fields’ and Jimmy McHugh’s On The Sunny Side Of The Street meanwhile turns out to be the slowest piece of romance, a sparkler carrying an ethereal dialog between all-encapsulating strings and sunset horns veiled in pongee, whereas the finale The Lonesome Road by Gene Austin and Nathaniel Shilkret genuflects one last time before an uplifting laissez-faire attitude akin to Singin’ In The Rain. Rhythmic horn fanfares and slightly colder than usual string streams allow this interpretation to be a glorification of a rainy afternoon in the street… as inspected from the sky.

Street Scene is an album that can be summed up as follows: Slatkin by the numbers. And that is a very good thing. This short description omits important pillars and constituents however. First and foremost, the album’s essence prospers and falls with the attached concept of aural street photography, and it is here where Street Scene both falls short and delivers more than expected, depending on the viewer’s very own angle. There might not be any field recordings of bustling street activities anywhere near the record, nor is there the feeling of pressure, hectic or frenzy. Slatkin softens and blurs these pestering feelings, though as unwanted they might be, they do belong to the aura of a megacity after all. In this very regard, Slatkin’s approach fails miserably. Even Bob Thompson’s The Sound Of Speed (1959) is keen on delivering street noises and related field recordings in order to bring the tunnel vision or soothingly galloping horse to life. Slatkin shies away from such gimmicks and lets the strings speak, a noble endeavor.

The short description above additionally fails to mention the textural progress that certainly takes place as Street Scene moves forward: the brass layers take a stand and reappear more frequently on side B, the blotches of the harpsichord add a delectably raucous scapegrace to the space grace, and the revved up drums add a touch of unexpected Easy Listening antimatter. Vivacity is all over Street Scene which remains a great symphonic Space-Age artifact to own, just don’t expect depictions of those streets that rely on reality. Although it is not an Exotica record at all, Felix Slatkin’s LP harbors similar techniques of blurring the (sky)lines. Unfortunately, the rightsholders of the Liberty back catalog have not yet decided to remaster this gem and deliver a pristine digital version of it, as is the case with many of Slatkin's other albums, but Street Scene appears regularly on eBay and other marketplaces.

Exotica Review 361: Felix Slatkin – String Scene (1961). Originally published on Jul. 26, 2014 at AmbientExotica.com.